Retail's Reckoning: The Great Fragmentation

By Michael Dart, A.T. Kearney

In our new book, Retail’s Seismic Shift, Robin Lewis and I describe a retailing world split open by the perfect storm of societal, demographic, and macroeconomic factors conspiring to drive down consumer demand at the precise moment the world is awash in excess supply.

One of the big forces behind this devastating supply-demand imbalance, and a key variable in how retailers will react to it, is an unprecedented level of fragmentation. If you think of yesterday’s mass market as a glass bowl, that market today is shattered into a thousand small fragments.

This incredible consumer fragmentation is impacting supply and demand — dampening demand (in the absence of major trends, consumers feel less compulsion to buy) and, with the emergence of niche markets, enabling start-up companies to satisfy these idiosyncratic tastes which once again increases supply.

For many years the prevailing theory has been mass brands can serve mass markets. But available data suggest a move toward an infinite number of discrete consumer segments. People will look for niche brands that are intensely relevant to their needs and provide a clear emotional connection. In fact, a by-product of the growing oversupply is that new brands are appearing almost daily. Unlike megabrands of the past, these brands and retailers will be multifaceted and diverse — each with a distinct position and set of identifiers — to target a smaller and smaller niche of consumers.

By definition, these niches will be more personal and authentic. Think of the disappearance of logos that once were prominently displayed on everything — at their peak in the 1990s, branded logo goods accounted for more than 40 percent of fashion purchases, but that fell to less than 10 percent by 2014.

Several drivers of this fragmentation suggest it will not end anytime soon. The trends in fragmentation pose a direct threat to every mass market, as well as the supply chains designed to fulfill them.

- Psychological Drivers

The most important contributor is the underlying psychological force that governs purchasing behavior and attitudes: the need for high self-esteem and social status. An environment in which you can use fashion and products to separate yourself from members of other groups is likely to have smaller hierarchical structures in which more people believe they are at the top or otherwise belong.

The desire for rebellion and status is driving a constant flow of new brands that capture a unique identity. As soon as a brand gets too big, new members or fans lose the ability to achieve status and go looking for something new. This cycle of creation and decline is deeply embedded in our psyches and drives consumer and brand fragmentation.

- Five Generations Under One Roof

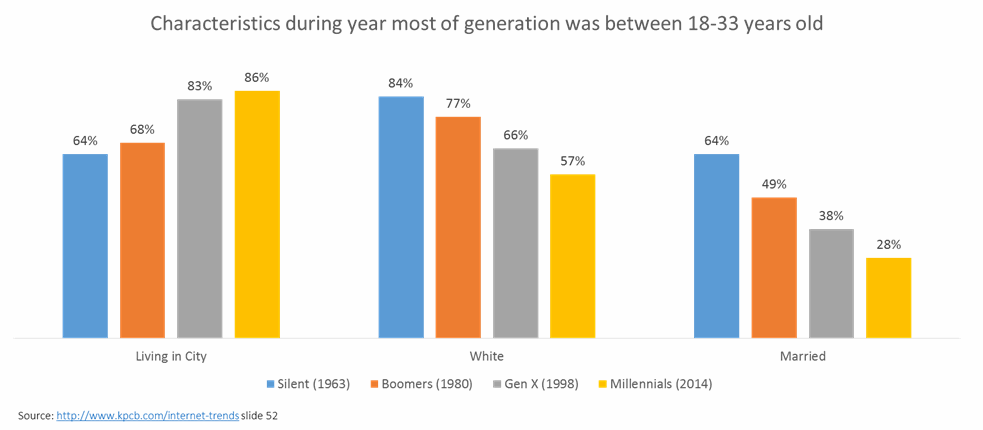

The second clear-cut trend is we are entering a period when the marketplace and workforce will host five distinct generations at the same time, as shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Generations became more urban, less white, and less likely to get married.

- A Widening Income Divide

As income inequality grows, the wealthy and the middle class consume a different mix of products changing the pattern of demand. The bottom 10 percent of Americans by income devote 42 percent of their spending to housing and 17 percent to food. In contrast, the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans dedicate only 31 percent of their spending to housing and 11 percent to food.

Although incomes are flat in almost every metropolitan area, consumer experiences vary quite dramatically by locality. The 10 metro areas that took the biggest wealth hits from 2000 to 2014 have one factor in common: a greater-than-average reliance on manufacturing. These areas saw a steep drop in the number of manufacturing jobs from 2000 to 2014, a sector that contracted 29 percent nationally. Making matters worse, jobs lost in manufacturing were not always replaced by others as overall private sector employment fell in these 10 areas with declines ranging from 3 percent to 25 percent. This is compared to a 5 percent overall in private sector employment in the U.S. as a whole.

These regional differences help explain the anger expressed in the 2016 presidential election and are a reminder retailers and brands speaking to a national market are likely to miss regional and community differences.

Income inequality shows no signs of abating. Between 2016 and 2026, the share of households earning $25,000 or less a year — putting them below the median household incomes of countries like Mexico, Venezuela, and Romania — will increase by 5 million people, to 20 million. This bottom 15 percent will fuel the continued demand for thrift stores, grocery discounters, and extreme off-price retailers.

- A “Majority Minority” Nation — In More Ways Than One

Already, many large cities are “majority minority,” meaning the nonwhite population is more than 50 percent of the total, or that no one ethnic group has a majority. Gen Z is the first majority minority generation — by 2026 only 48 percent of Gen Z will be white, whereas 27 percent will be Hispanic, 14 percent black, and 6 percent Asian. Ninety-five percent of population growth between 2016 and 2026 will be driven by nonwhite ethnic groups.

Younger generations are less likely to get married and have kids and more likely to live alone. We’re also seeing an increase in the number of single parents, many of whom put a premium on convenience. Time-starved single moms (predominantly) are looking for retailers and brands who understand the pressures in these women’s lives.

Clearly, the thought a flat world (or one that’s increasingly globalized, interconnected, and fast-paced) meant our experiences would converge is proving to be wrong.

How Retailers Should Respond

As noted earlier, fragmentation is inhibiting retailers’ ability to drive mass demand and increasing the supply of many niche brands or products.

The implications for retailers are clear. First, they must cater to changing demographics. Brands will also have to reckon with a fast-proliferating set of consumer preferences that are creating an infinite number of finite markets.

Even an iconic American brand like Levi’s has fallen victim to this trend. The company was flying high with $7.1 billion in sales as recently as 1996 — making it bigger than Nike at the time. But its consumers were picked off by a host of smaller competitors coming from all sides — super premium brands like 7 for All Mankind and True Religion from the top and value-oriented brands like Lee and Wrangler from the bottom. Levi’s sales bottomed out at $4.2 billion in 2003 and haven’t grown much since, hitting $4.6 billion in 2016.

Retailers will need to do even more to make themselves compelling and convenient to an increasingly diverse set of niches. Retailers have found vastly different preferences by neighborhood — within the same city — for things like convenience, ethnic foods, and healthy product offerings, demonstrating fragmentation drives real purchasing differences.

Americans are now living in the fragmented states of America, and the implications for retailers and brands are life altering. In Retail’s Seismic Shift, we explore more of the changes sending shockwaves through our industry and profile retailers who have what it takes to meet this tremendous new challenge.

About The Author

Michael Dart is a partner in the private equity practice of A.T. Kearney, a global strategy and management consulting firm, and author of Retail’s Seismic Shift (St. Martin’s Press, 2017). He can be reached at Michael.Dart@atkearney.com.